Nemo

They were woken by an unusual variation in the gentle swaying of the ship and lifted themselves drowsily from their bunks to the portholes behind them in time to see the motor launch pull away across the dawn with six of their seven warders on board.

They were woken by an unusual variation in the gentle swaying of the ship and lifted themselves drowsily from their bunks to the portholes behind them in time to see the motor launch pull away across the dawn with six of their seven warders on board.

This was in itself unusual. They were never left unguarded. Refugees, asylum seekers, illegals, misfits, political recidivists and non-compliants, two hundred and fifty of them in the lower decks barely above the water line, they had too little in common and too much to fight over to be left alone.

The humming of the launch was gradually replaced by a sound they could not identify, which seemed to come from the deck above them accompanied by a vibration in the air that rose to fill the narrow space between them and finally invaded the whole vessel.

Suspended appeals, tattered hopes, fears for their captive families and mutual suspicions had enforced the good behaviour of its human cargo – who could tell which neighbour was an informer? – but now they rose as one and beat their fists on the doors, clamouring to be let out or given their paltry rations at least. Who was in charge here? Someone screamed that the water was rising. And that infernal noise howled on.

Six young men ripped a stanchion from the rafters and battered at the steel door, which finally bent and fell off its hinges. The prisoners raced past the exterior freight entrance through which they had been boarded in handcuffs, the metal staircase clanging beneath them. A narrow pass door led them into a world they had never dreamed of.

Beneath royal insignia of some kind, mahogany double doors opened into a state dining room where an endless table was laid for fifty visitors, their menus printed on gold embossed cards beside the acre of silver cutlery laid out for each velvet padded chair. Of guests, no trace.

Some wandered in disbelief, others backed off into the galley kitchens lined with jars and tins. They scooped, they tasted, but the beans and pulses ran through their fingers like plastic confetti and the plaster loaves stuck to their palate. Nothing was real. Except the dust.

Angrily they searched the prow. A carpeted corridor gave onto bedrooms on each side and led eventually to a suite with double bed beneath a silken canopy. Despite rage and despair, they fell back in awe, staring at the once black-and-white now yellowing photographs in ormolu frames of noble people they felt they should recognize but did not, a generation their grandparents had spoken of in hushed tones of adulation. Beside the tilted dressing table mirror, a happy family waved from the ship’s railing above the letters B…annia, the missing letters masked by a banner of red and blue crosses.

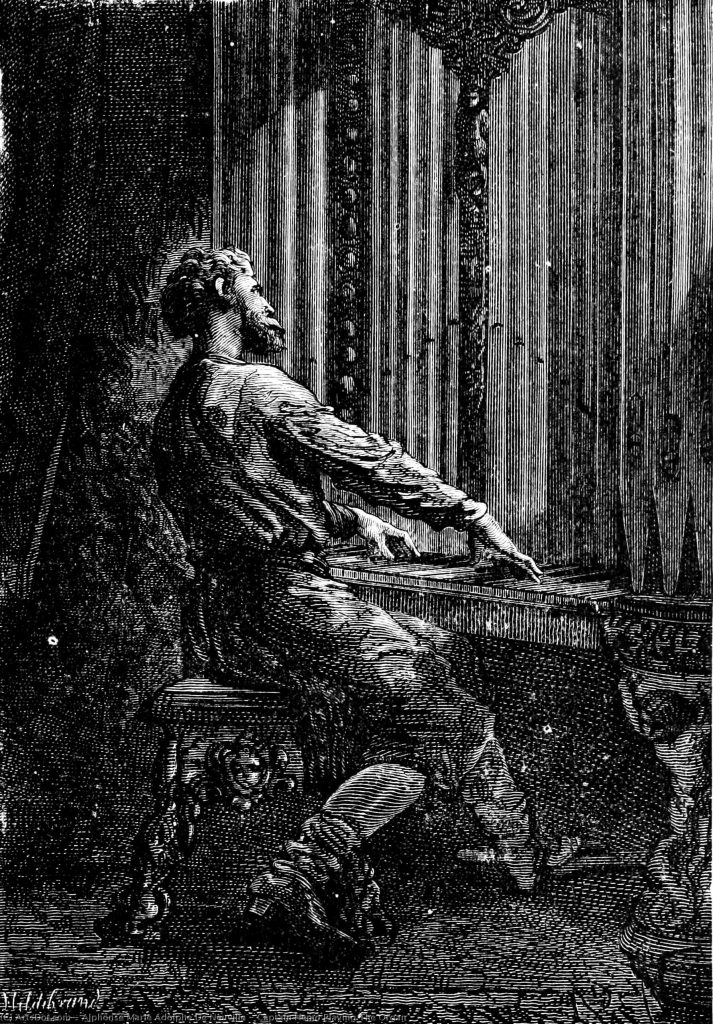

Impatiently the youngest hurtled onward up matching flights of double helix wrought iron stairs to a balcony that gave onto a ballroom the length of the ship, its doors flung open for the majestic dance to come. At the far end, a lone figure was bent over what seemed to them like a scullery serving bench beneath a pyramid of silver heating pipes, but no food issued from his kitchen, only that noise, now trebled. He seemed unaware of them as they cautiously advanced across the polished parquet and finally stood at his shoulder.

“I knew this was here,” he muttered. “They wouldn’t let me in. Subversive, they said.”

His fingers flew up the keyboard like seagulls swooping on water. “I wasn’t made to be a prison guard, I’m a musician, I set people free. But no one paid. Not a penny. To hear me play or anyone else. No performance. Nothing live. They just switched on the feed and forgot where it came from.”

“We’re sinking,” they said.

“I know,” he responded and played on.

© Gareth Jones 4/10/20